Partly Cloudy, 68° F

As a child, Takei was interned in a Japanese American confinement site with his family, according to the Heart Mountain Foundation. Takei visited the Heart Mountain site Tuesday. He was accompanied by his husband, Brad, and the writers and producers …

This item is available in full to subscribers.

The Powell Tribune has expanded its online content. To continue reading, you will need to either log in to your subscriber account, or purchase a subscription.

If you are a current print subscriber, you can set up a free web account by clicking here.

If you already have a web account, but need to reset it, you can do so by clicking here.

If you would like to purchase a subscription click here.

Please log in to continue |

|

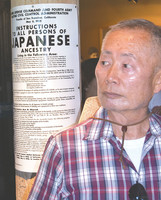

Actor George Takei, also known as Hikaru Sulu of the original “Star Trek” television series and movies, is recognized across the globe. But when visiting Heart Mountain Interpretive Center earlier this week, he wasn’t there as a star — rather, he was one of several Japanese American internment survivors who shared their stories.

As a child, Takei was interned in a Japanese American confinement site with his family, according to the Heart Mountain Foundation. Takei visited the Heart Mountain site Tuesday. He was accompanied by his husband, Brad, and the writers and producers of “Allegiance,” a Broadway play Takei acted in that examined Heart Mountain internees’ refusal to comply with their draft notices.

The Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor Dec. 7, 1941.

President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 Feb. 19, 1942, setting the stage for the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans.

Takashi Hoshizaki, Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation member, was 16 when his family was shipped from Hollywood, California, to the Heart Mountain Relocation Center.

Hoshizaki’s father lost his business, a grocery store, because of the relocation. Fellow Japanese Americans were forced to sell everything at fire sale prices.

A new car in 1942 fetched around $1,000.

The Japanese seller would be lucky to collect 15 percent for an automobile worth $300.

“Well,” the buyer would say. “We’ll give you $50 for the car.”

Takei was 5 years old when he was sent to a camp. He recalls an atypical Arkansas snow storm when he and other boys built an igloo from snowballs. He also remembers being warned to watch out for water moccasins.

Life in camp wasn’t too tough for him, but it was very degrading for his parents, Takei said. The outrageous violation of Japanese Americans’ constitutional rights is a chapter in American history, Takei said.

“I’m so sorry,” said a white woman who was close to tears while she hugged Hoshizaki.

The center describes life in the camp. “The story is very well presented here,” Hoshizaki said.

Draft

Hoshizaki’s memories of camp life are relatively upbeat, like a kid who enjoyed his stint at summer camp. But, good times being a Boy Scout leader or playing baseball with his buddies did not sway his opinion of the unconstitutional incarceration of himself and his fellows.

Young Japanese American men in camps received their draft notices just like countless Americans across the country, including Hoshizaki.

Hoshizaki was one of the 63 “Resisters of Conscience” at Heart Mountain who contested the legality of confinement by refusing to serve in the military in 1944. They were labeled “draft dodgers,” he said.

Return their civil rights and reunite their families, Resisters of Conscience said, “... and we will gladly serve,” Hoshizaki finished.

The federal government prosecuted.

“We were given a three-year sentence,” Hoshizaki said. He was out in two years for good behavior.

“You’re heroes,” Takei said.

Not all Heart Mountain inhabitants or those from similar camps refused to serve. The 442nd Regimental Combat Team was composed of Japanese Americans.

Eight hundred men from Heart Mountain served during the war and 15 died, Hoshizaki said.

When a group of 200 soldiers were stranded behind enemy lines, the 442nd went to their aid, Hoshizaki said. “It cost 800 (Japanese American soldiers) casualties to rescue 200.”

President Harry Truman pardoned the resistors in 1947, said Hoshizaki, who ended up serving in the U.S. Army during the Korean War.

Hoshizaki said he still lives in Hollywood, right across the street from his childhood home. And, like many Los Angeles locals, he complains about traffic.

Tak Ogawa of Powell was drafted during World War II. After the war, like many veterans, he homesteaded in the Heart Mountain area and is still farming, said his friend, Joe Baker.

Many Heart Mountain homesteaders bought Heart Mountain barracks for their farms.

Ogawa donated his to the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, Baker said.

Bigotry now and then

Now, some people consider all Muslims terrorists because of horrendous acts of a few radical Muslims and African Americans and police are being killed.

The war years were an irrational, hysteric period in American history, Takei said. “... intensely racist time.” Now the same attitude has surfaced pertaining to black people in addition to Muslims.

“JAPS KEEP OUT YOU RATS,” said a sign in an American store window after Pearl Harbor.

“All of a sudden, I’m beginning to understand what racism is,” said one lady in a film at the center.

“We were not free,” said another voice in the film. “My God, we’re in a concentration camp.”

With the end of the war, Japanese were set free with $25 in their pockets, and many had no homes to return to. Still, they endeavored to reboot their lives.

Takei recalls elementary school. His teacher referred to him as, “The Jap boy,” he said, still feeling the sting. “What had I done to her to get this vulgar word spat at me?”

Hoshizaki was the first student to get his high school diploma at Heart Mountain. After the war, he attended college to earn a doctorate. Most people didn’t know who the original resistors were and he make no effort to recount his past while in school, Hoshizaki said.

Old haunts

Brian Liesinger, executive director of the Heart Mountain Foundation, served as a tour guide of the center. “We are celebrating our fifth anniversary,” he said.

Sam Mihara, Heart Mountain Foundation Board director, also lived in a camp during World War II.

One center exhibit re-creates a tiny room where a family lived. One item that later generations may not recall availing themselves of was a chamber pot.

When it was bitter cold with the wind blowing 50 mph, barrack residents opted for the pot, Mihara said.

“I recognize these beds,” Takei said, pointing out a narrow cot with a scratchy wool green Army blanket.

Outside, Liesinger gestures toward a barrack recently returned from the Shell area.

“This is the original barrack,” he said.

Plywood now sheaths the structure, but originally, tar paper covered the board exterior. The green lumber cured and contracted, allowing cold air and wind-driven dirt to blow freely into the huts.

Today, he wants the world to know the plight of Japanese Americans during World War II. “We’re trying to get the story out so it won’t happen again,” Hoshizaki said. “We’re facing the same type of situation.”

Inspired by the life experience of George Takei, who played Mr. Sulu in the original “Star Trek” series, “Allegiance” is a story of a Japanese American family that was relocated to the Heart Mountain Relocation Camp during World War II.

The Broadway musical “Allegiance” opened in New York in November 2015 and closed in February.

The story is based on Takei’s family, though his family actually was imprisoned in another camp.

According to the “Allegiance” website, “Despite the injustices he and his family suffered, George harbors no resentment or anger.”

The website said each performance of “Allegiance” is a tribute to the fortitude of the Takei family and to the 120,000 others like them “who endured with inspirational grace and dignity.”

“Even younger Japanese-Americans don’t know about it, because those that experienced the internment — the pain, the suffering, the sense of loss and degradation and humiliation, didn’t want to inflict that pain on their children,” Takei said in a BroadwayWorld.com story.